Raiden: The Beginning

Posted onI always had an interest in computer graphics. As a kid, I was amazed by the 3D video games of the time. The experiences I had back then inspired me to pursue software development as a profession. However I did not bother to look into the inner workings of computer graphics until recently. The urge to create inspiring games as I had when I was a child, and the computer graphics class I took last semester motivated me to deep-dive into the vast world of triangles and spheres.

Anyone who is willing to learn more about graphics should probably start out with writing a raytracer. You write code that is simple (from a programming perspective) yet can produce awesome results without relying on any third-party graphics API. Therefore it was mandatory for me to start writing a raytracer from scratch. Here I present you, Raiden. Starting with this post, I will document my development process of Raiden. I will start from the very barebones of a raytracer and hopefully make it into something that I could be proud of in the future, and more importantly, know more about computer graphics in the end.

All the benchmarking is done on my personal laptop, which features an Intel i5-7300HQ processor. Also the project is implemented in C++. However, the performance of a raytracer mostly depend on the efficiency of the data structures and algorithms used. Therefore I believe that any language is equally viable unless you go for an industrial-grade raytracer – which I assume you would not bother reading this if you did :) Without further ado, let’s jump right in!

Implementation

I normally write all the code myself in the projects that I am serious about. However, to start working on the actual graphics stuff, I opted to use some external libraries in several parts. Namely, stb_image to write PNG images and tinyxml2 to parse scene files given as XML.

I started out by just creating a color gradient and writing it to a file. It took a surprisingly long time. Probably because I was juggling between several different designs regarding the memory representation of the image. I decided to go with a 1D std::vector of Color structs, which consist of 3 uint8_t values for R,G and B. The resulting image is shown below:

In the next step, I started to implement basic raytracing structures, starting out with rays. A lot of vector math was going to ensue, therefore I found it handy to have a simple math library under my belt. I implemented a 3-float vector (vec3f as it is common in the graphics circles) and some basic vector functionality like dot-product and normalization. Later I created a “skybox” to test these out. It casts rays to each pixel coordinate and linearly interpolates between blue and white color by the y-value of the normalized ray. Here is the result:

It is time to implement our surfaces. Sphere is the easiest of all, so I started with it. I had planned to implement basic features using spheres, and later implement other surface types. Calling our object types “surfaces” may not be pedantically correct, as calling them surface neglects the fact that they have a volume. However, it did not matter for my simple raytracer and it felt like the best name among other options. After implementing a ray-sphere intersection routine, here is our rising sun up in the sky:

It is important to notice that at this point almost everything is hardcoded. I did not read from scene files yet. Camera is assumed to be at (0,0,0). Aspect-ratio is hardcoded so is the image resolution.

Up next I implemented a very basic material system. It consisted of just a single color. In addition to that, I also wrote a diffuse shading function. I did not care about performance or proper organization at this point. Therefore bunch of stuff was quick-and-dirty hacks. I just wanted to see something on my screen as soon as possible. Here is a render of two spheres, with diffuse shading applied:

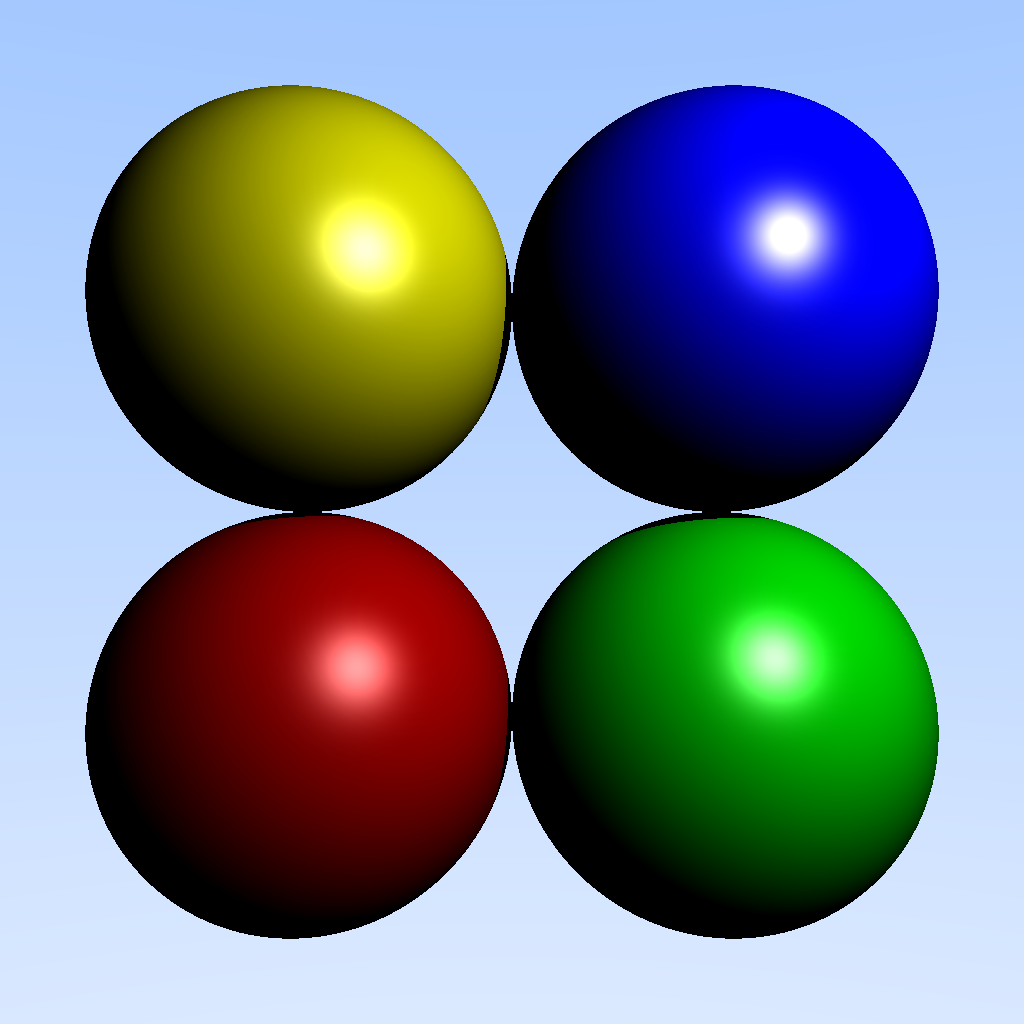

Next logical step after diffuse shading was the addition of specular shading. At this point hardcoding everything started to become troublesome, therefore I integrated the XML parser and started reading from the scene files. During the process I somehow broke the working code of diffuse shading and the results started to look as if they were rendered with a cartoon shader. At the time I could not find the problematic piece. After some time I realized I was working with color range between 1-255, and somehow passing this to a function that expected the colors to be normalized (in range 0-1). This also caused my specular shading to be super bright. Here is the faulty render of four spheres:

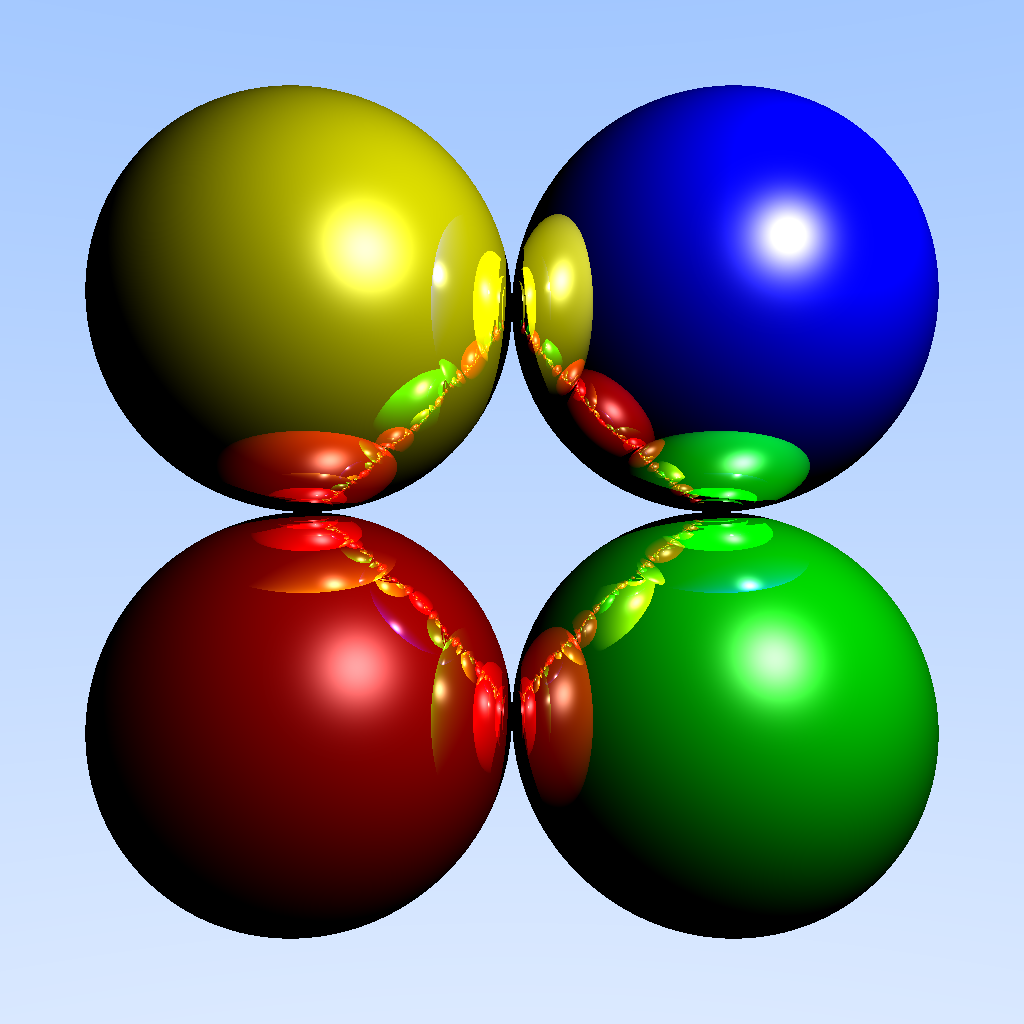

I fixed that mistake, and added shadows, which was only a few lines of code. Here is the same scene with the fix and shadows. You can see the falling shadows at the touching parts of the spheres:

A mere ~10 lines of code and the results really start to shine with the added reflection:

At this point I felt like I saw enough spheres in two days, and wanted to add triangles (which means meshes too). I experienced the most hair-pulling moments at this phase. Because I wrote all my code to expect sphere, and unifying different objects under a single surface interface required a major reorganization in the codebase. During the process lots of subtle bugs occured, long walls of compilation errors were read, and lots of coffee was consumed. In the end, I could get the same outputs as before, but now with the new Surface interface.

On top of the the surface interface, I started writing the triangle class and ray-triangle intersection routine. Everything went smooth as the code was more organized now than before.

Rest of the implementation was removing more hardcoded parts, fixing small bugs (self-shadowing objects and unexpected shadows comes to mind) and reorganizing code.

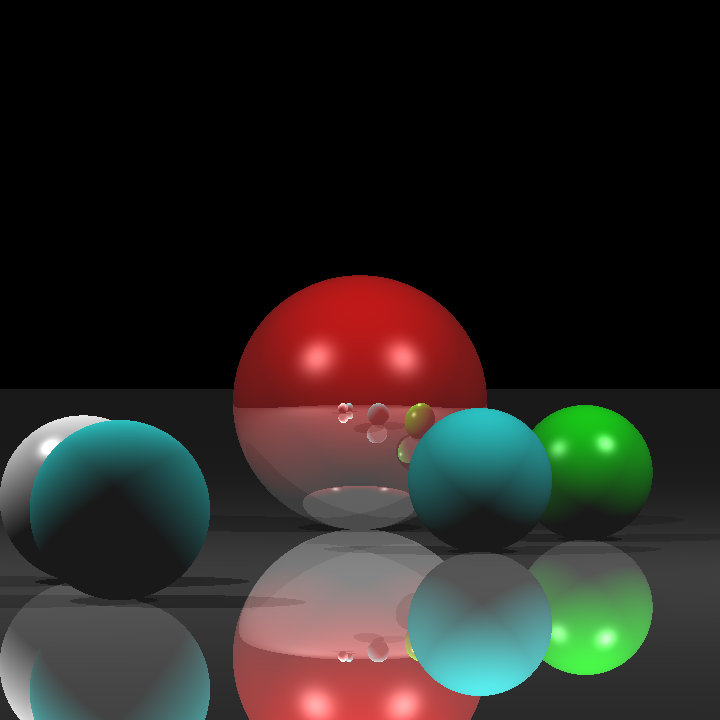

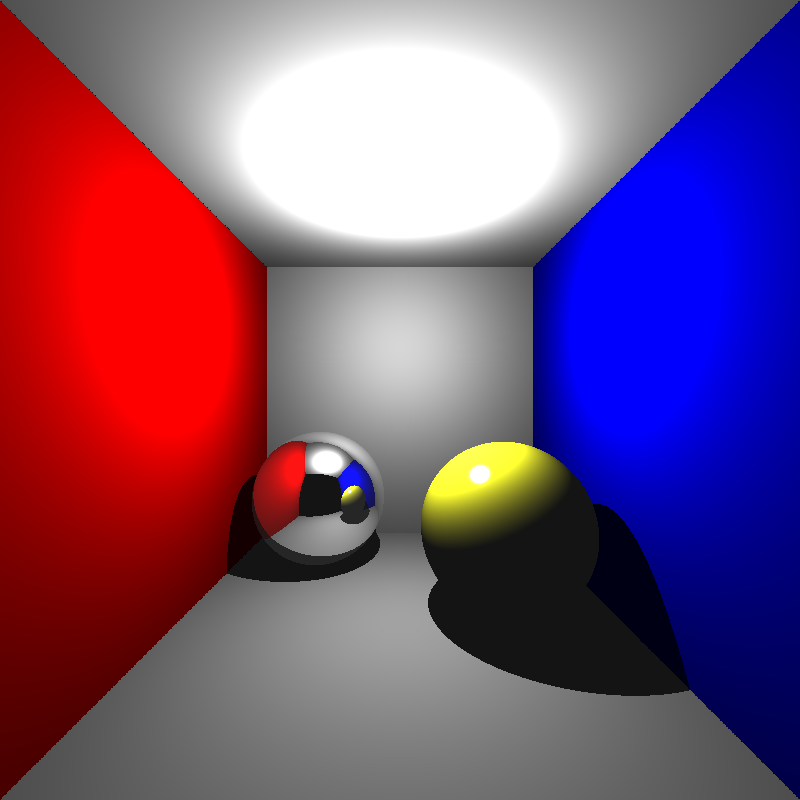

This is the current state of Raiden. Here are a few fresh renders:

Stanford bunny, 512x512, 22.116 seconds

Spheres, 720x720, 0.678 seconds

Cornellbox, 800x800, 0.987 seconds

What’s Next?

The first planned feature is the addition of refractive surfaces, such as glass-like objects. Some other work to be done in the near future are:

- Acceleration structures, more specifically BVH

- Parsing .ply objects

- Multisampling

Computer graphics is really a wonderful world with very satisfying results at the end. I am excited about the future of this project. I will see you in Part 2, with some new and great additions to Raiden. Thanks for reading and happy coding.